STUTTGART, Germany — Yasmin, a Yazidi woman who survived rape and torture at the hands of the Islamic State (IS), made international headlines seven years ago after dousing herself in kerosene and lighting a match. The flames melted her nose, eyelids, ears, lips and chin and fused her fingers into an unusable mass. Today, some 160 surgeries later, Yasmin, 24, is a poignant symbol of the resilience of hundreds of Yazidi women who were offered sanctuary in Germany where they are shattering the boundaries of their patriarchal Middle Eastern culture and seizing control of their own lives.

“I want to study law, to become a lawyer,” Yasmin said in fluent German over coffee in Stuttgart’s main square. Clad in a black jersey top, a matching chiffon skirt and a rhinestone-studded belt, Yasmin has recovered her facial features crafted from her own skin and ribs. Her fingers are functional, her nails varnished in a coral color. Yasmin flashes an engaging smile, saying she is very excited as she will soon be getting new ears.

Yasmin’s self-immolation at a displacement camp in Iraqi Kurdistan’s Dahuk province was triggered by a flashback. She heard voices outside her tent and believed IS militants had come back to torment her. She decided at that moment that death was a better fate. “The path to recovery is hard but these girls are incredibly brave. Knowing what they have been through, it’s miraculous,” observed Jan Kizilhan, an ethnic Yazidi trauma psychotherapist who is treating the victims. When he first encountered Yasmin, she was lying on a mattress in blazing temperatures at an unfinished construction site in Dahuk. “She looked at me, smiled and offered me tea.”

Kizilhan was in Iraqi Kurdistan as part of Operation Sonderkontingent, or “special contingency,” a $106 million scheme involving the transfer of 1,100 Yazidi women and child victims of IS to Germany in 2015 and 2016. Their stories continue to haunt him.

Undated photo of Yasmin prior to her captivity. (Courtesy of Jan Kizilhan)

One case stuck with him more than any. It's that of a young woman, Tulay, whose year-and-a-half-old daughter was stuffed by her captors into a tin can and suspended from a rope strung across the balcony of the apartment where they were being held. The sun shone directly on the can, literally baking the child inside it. Her tormentors gave her just enough water to keep her alive, then finally thrust the child into icy cold water, causing her eyeballs to pop and her skin to burst. When she didn’t die, they broke her spine and then dumped her on her mother’s lap — “punishment” for Tulay’s failure to “properly” recite the Quran.

Tulay and her surviving son and daughter were brought to Germany as part of the group. Tulay works in a restaurant and has found a new balance. Kizilhan recently checked in on the family. “The children were laughing and drawing pictures for me,” Kizilhan said. “I felt pure joy.”

The majority of the Yazidis were ferried to Baden Wurttemberg, a wealthy state in southwestern Germany where a government that is still led by Winfried Kretschmann of the Green Party embraced the idea of rescuing them. The operation was conducted in top secrecy as IS continued to unleash terror attacks across the European continent. “At first we flew them via Istanbul. We then realized this was adding to their trauma as they were exposed to men and women who looked and dressed like their captors, so we chartered special flights and flew them directly here,” recalled Michael Blume, the state official who oversaw the operation and is currently leading efforts to combat antisemitism. Yasmin was transported in an air ambulance.

Michael Blume, the German official who oversaw the transfer of Yazidi survivors to Germany, on July 17, 2023 in Stuttgart, Germany. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

“Our program has been a huge success. Most of these people will give back to Germany what Germany gave to them,” Blume said in an interview at a sprawling mansion in the hills above the city center, which is the seat of the local government. Married to a Muslim Turk, Blume exudes pride as he describes how fast his former wards have adapted. “Just two attempted suicides, that’s it. Nobody has killed themselves here in these eight years,” Blume said, whereas back in the camps in Iraq, an untold number of Yazidis succumbing to depression have taken their own lives.

Child interrupted

In Stuttgart, the “Sonderkontingent Yazidis" have learned German, obtained high school diplomas, enrolled in university and found jobs. They typically experience less of the racism endured by other migrants. This is because “the German taxpayer understands that their situation is unique, that they have truly suffered” and therefore takes pride in offering them a haven, Blume explained. The fact that the majority are women and children is an added bonus. For a nation stained by the Holocaust, embracing the Yazidis feels good.

Nobel laureate Nadia Mourad was the first to tell the world of the horrors she and fellow Yazidi women captives lived through, searingly chronicled in her bestselling memoir, “Last Girl.” A growing number are coming forward with their own stories. Farhad Alsilo, 21, is one of them.

Farhad was 12 years old when he saw his father executed by black-swathed IS militants and four of his sisters taken away in his native Tell Azer in the Sinjar district of Iraq. Also known as Shingal, the area is where the bulk of Iraq’s Yazidis resided until IS embarked on its killing spree across the region in August 2014 that left 7,000 Yazidis, mostly men and boys, dead in the course of a few days. Thousands remain unaccounted for. Some 2,700 are women.

Farhad has just graduated from high school and goes from one local classroom to the other to tell his story. “Students ask me a lot of questions. They are interested because unlike their teachers I am describing something I lived through myself.”

Farhad Alsilo and his sister Khaleda at the Kizilhan residence in Stuttgart, Germany, July 18, 2023. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

He has written a book called “The Day My Childhood Ended” and has 20,000 followers on Instagram. During a recent afternoon at Kizilhan’s apartment, Farhad sat around the kitchen table with one of his sisters, Khaleda. “This is my country. I came here at a young age. Germany offered me great opportunities,” he said in flawless, unaccented German. Khaleda, who was held by the jihadis for five months, nodded in agreement. She fell in love with and married a fellow Yazidi in Stuttgart and has a baby girl. “I am happy here,” she said. Khaleda plans to resume work soon as a cashier. Farhad has applied to college to become a mechanical engineer.

Yasmin says she will seek an apprenticeship in a lawyer's chamber once her medical treatment is completed. She has a further 50 surgical procedures to go. Unlike Farhad though, she says she lacks the mental strength to lobby on behalf of her people. “I often feel angry and sad,” she said. People have called her “a monster” and a “freak.” An Arab bypasser said she looked like a monkey, not realizing that she understood. What hurts her the most is when children become frightened by her appearance. “Beauty lies within us,” she said.

Others are wracked by what Kizilhan terms “survivors’ guilt.” Another issue is split families. Only 30 men were granted permission to come under Operation Sonderkontingent. Germany’s immigration laws are toughening amid a backlash against former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s open-door policy that saw over a million Syrians granted asylum. Reunification is increasingly out of reach.

Not without my child

With an estimated 200,000 Yazidis, Germany is home to the largest community of this ancient ethno-religious sect outside their traditional homeland in the Levant, where for centuries they have faced enslavement, ethnic cleansing and ostracism as “devil worshippers.” Many came as part of the first wave of guest workers in the 1970s. A further wave fleeing repression in Turkey and Iraq in the ’80s and ’90s ensued.

Germany is the first country to have tried IS members — with Amal Clooney serving as the victims’ counsel and the sole one to have convicted any for war crimes against the Yazidis. In January, Germany’s lower house of parliament, the Bundestag, voted to join 18 other governments and international bodies — including the United Nations — that formally label the mass slaughter of thousands of Yazidis by IS a genocide. The tragedy is commemorated worldwide on Aug. 3.

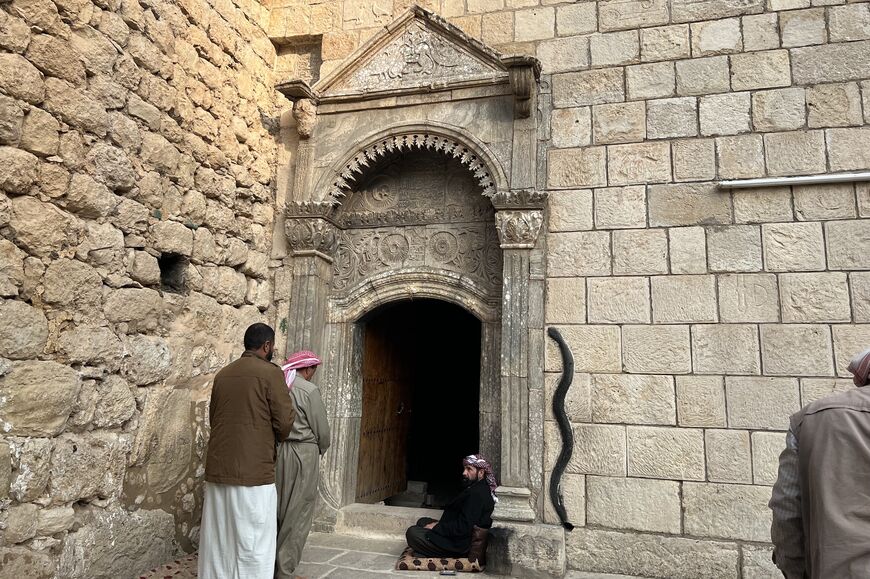

A man inside Lalish, the Yazidis’ holiest shrine in Dahuk, Iraq, Nov. 18, 2022. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

With more than 200,000 languishing in camps in Iraq in dire conditions, Baden Wurttemberg has tentative plans to bring over more Yazidi women. The government wants in particular to salvage those who bore children by IS fighters. But in doing so, it has stepped into something of a minefield. While the Yazidis’ top religious authority, the Spiritual Council, has welcomed back so-called “sex slaves,” it has rejected children fathered by their Muslim captors.

Thus, rather than abandon their children, an unknown number have stayed behind in internment camps in northeast Syria where the families of IS militants are being held. And since Iraqi law requires fathers to authorize passports for minors, this leaves such children in legal wilderness and unable to travel.

“The politics have changed. Now you need the consent of Baghdad to take out Yazidis,” Blume observed. Previously, that of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) sufficed.

Germany’s first woman foreign minister, Angela Baerbock, a Green who has vowed to introduce “a feminist foreign policy,” railed at the rules during a recent trip to Iraq that included a visit to a Yazidi camp. “Like all children in this world, these children have human rights,” the top diplomat said. “That also means the right to their own surname.”

A new kind of hell

Such rebukes do not sit well with Yazidi leaders who deeply oppose their flock’s efforts to leave Iraq. However, the alternative — returning to their ancestral Sinjar — seems virtually impossible. Sinjar remains in political limbo with a patchwork of Iran-backed Shiites and militias controlling the region that is strategically wedged between Turkey and Syria. Turkey periodically carries out airstrikes on the grounds that outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party militants are active in Sinjar. Civilians have been killed together with the alleged fighters.

There is no mayor, functioning administration or adequate health care. “Even the most basic and mandatory bureaucratic procedure, that of acquiring a national identity card, has become a new kind of hell,” said Mirza Dinnayi, an award-winning Yazidi activist who took a leading role in Operation Sonderkontingent.

Worshippers outside the Yazidis’ holiest temple Lalish in Dahuk, Iraq. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

“The problem,” Dinnayi noted, is that “the central government in Baghdad has no national plan to repatriate these people.”

A deal struck between Baghdad and the KRG in 2020 was meant to have led to the disbandment of all armed groups and the return of displaced Yazidis. But it failed mainly because the community itself was not properly consulted. “With political will, this can be redressed [and] the agreement amended,” Dinnayi said. “But there appears to be none.”

Transitional justice in Iraq “is simply not working.” A government scheme to compensate victims of the genocide is steeped in controversy. Women are expected to go before a judge in a packed courtroom and describe their ordeal in minute detail in order to qualify, forcing them to relive their trauma. The judiciary is filled with religious conservatives who take offense at the women’s claims. Many are, therefore, reluctant to go.

In 2016, Kizilhan founded the Institute for Psychology and Psychotraumatology at the University of Dahuk to train new therapists, the first of its kind in Iraq. Yet the lack of mental health workers equipped to treat victims remains a big challenge. Dinnayi recalls an instance when a Yazidi woman who was raped 17 times nearly came to blows with her male therapist. He “forgot his competence and accused her of ‘attacking my religion’” as she began “insulting Islam and the Prophet Mohammed.” “I was shocked by both,” Dinnayi said.

Against this grim backdrop, Dinnayi, Kizilhan and Blume agree that survivors are better off in Germany. “But we need to hurry,” Minnayi cautioned. “The welcoming atmosphere of 2015 is no longer there.”