From roads to routers: The future of China-Middle East connectivity

May 2023 Al-Monitor PRO Trend Report

3,513 words

Introduction

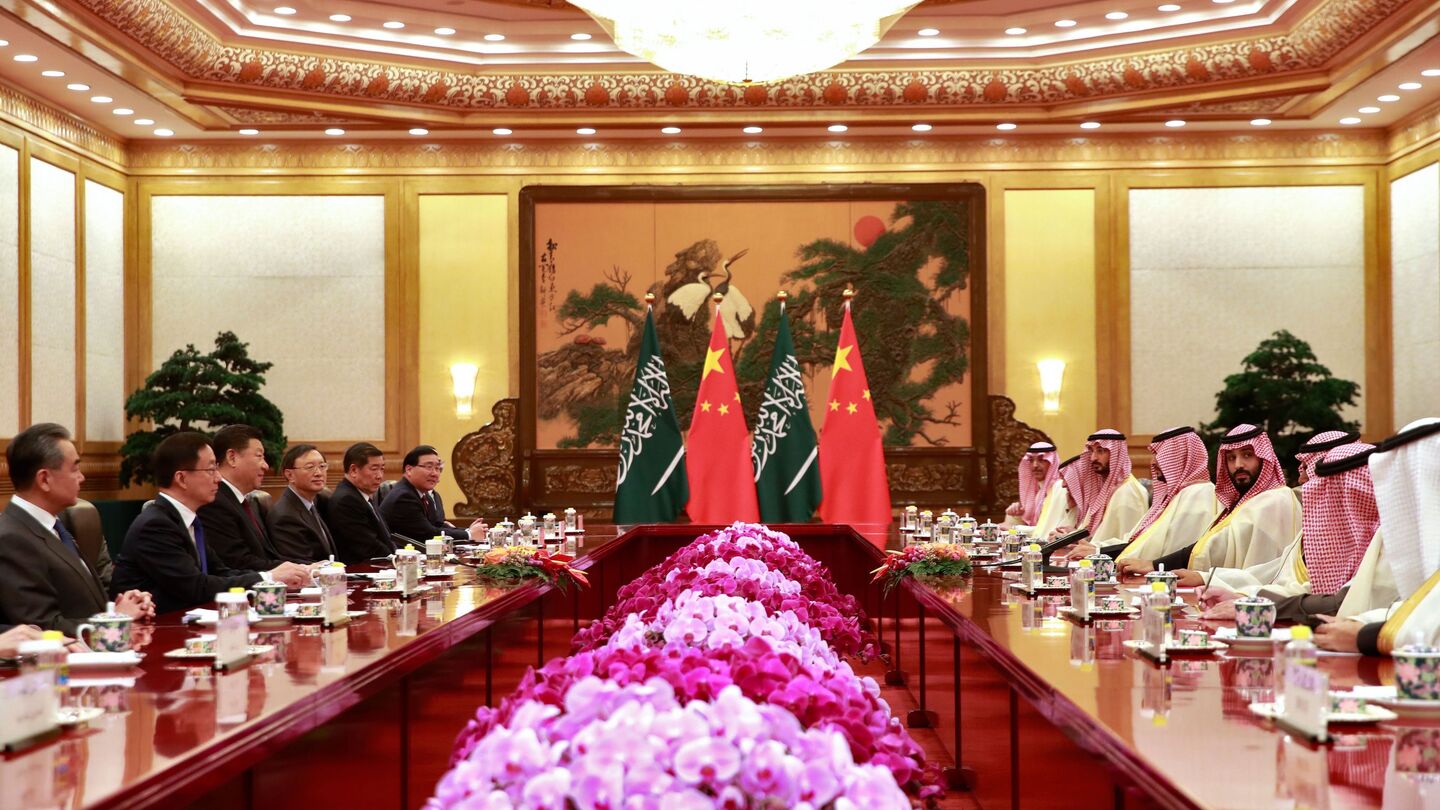

Chinese and Gulf state dignitaries have had a productive spring. On May 7, the UAE’s nuclear energy authority finalized three agreements with its Chinese counterparts to develop nuclear infrastructure in the Emirates. Beijing admitted the UAE and Kuwait to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization as “dialogue partners” just two days earlier. Saudi Arabia joined the bloc in late March, one week before reviving relations with Iran with the help of Chinese diplomats.

This signing spree may have surprised analysts a few years ago. Now, it reflects a truism in policy circles: China is deepening its engagement in the Middle East, and the region, by and large, is welcoming it. Beijing’s motivations have remained consistent over the past two decades. So too has its proclivity for economic integration (though recent forays into sensitive geopolitical quagmires signal a willingness and ability to expand its presence in politics).

Few experts expect this blossoming friendship to wither. But its form and focus is evolving. Sensitive to shifting regional dynamics, Beijing is adjusting how and where it involves itself. Once popular destinations for Chinese investment are falling by the wayside. Promising new connections are progressing in their place. Cheaper, tech-focused partnerships are attracting the funds and planning once dedicated to the grand, bank-busting infrastructure megaprojects that defined China’s aspirations for global connectivity. These shifts will dictate the Sino-Middle East and North Africa (MENA) relationship for years to come.

1. The State of Play

China began looking to its immediate west in the 1990s. Chinese manufacturers had kicked into gear, and the country’s economy thrived. Soon, the energy demands of its voracious factories outstripped supply. China craved new markets and new sources of fuel; the Middle East offered both.

“When you become the growing demand engine for oil purchases, you’re going to become more intertwined with countries that are vital to the supply of global oil,” Afshin Molavi, a senior fellow at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, told Al-Monitor.

The share of Chinese energy consumption fed by oil and natural gas has hovered between 25 and 30 percent since the early 2000s. Ever-growing domestic demand for both fuels has cornered China into a precarious reliance on imports. In 2019, China shipped in 72.5% of its oil and 40.6% of its natural gas (compared to 46.8% and 2% respectively a decade earlier).

MENA states — particularly Gulf countries — are China’s principal energy supplier. China sourced roughly half of its energy imports from the region in 2022 (down from almost 60% in 2002). Saudi Arabia has been its most bountiful provider, accounting for 14.4% of energy shipments to China last year. Iraq and UAE followed, each contributing around 8%. Over the course of two decades, MENA became a linchpin of the Chinese economy.

“Having cooperative partners and a secured, guaranteed [energy] supply is critical to China,” Charles Dunne, a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute, remarked. “MENA is a vital strategic region to them.”

As MENA fuel energized China’s industrializing society, Chinese goods packed the region’s shelves and warehouses. Trade flourished. By 2021, China was the top import supplier for the region’s five largest economies. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Iran sent most of their exports to Chinese ports that year.

This symbiosis intensified in the early 2000s. The connective tissue strengthened and diversified. Trade gave way to investments and generous construction contracts. Meetings between CEOs soon became meetings between presidents. China spent billions on energy and transportation infrastructure projects across the region. Chinese direct investments in MENA increased sevenfold between 2003 and 2009. Chinese delegations penned cooperation agreements with Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Egypt, Turkey and others. Beijing also took smaller yet significant steps on the multilateral level, establishing the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum in 2004 to coordinate crisis response and large, multinational initiatives.

“You now not only have oil flows and trade flows, but you have capital flows and heads-of-state flows,” Molavi observed. “It was a natural progression of commercial opportunities available to both sides.”

Xi Jinping imbued China’s approach to the region with a semblance of urgency and strategic cohesion. Xi premiered the Silk Road Economic Belt strategy in 2013, which was rebranded the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) a few years later. Beijing pitches BRI as a catalyst for global commercial, financial and diplomatic connectivity. What exactly this does (or doesn’t) encompass isn’t clear. Most experts classify the initiative as a loose amalgam of grand memoranda, pricey projects and strategic investments designed to boost Beijing’s economic and geopolitical power.

“From a conceptual standpoint, all of the foreign policy tools China is using in these regions — cooperation forums, strategic partnerships, special economic zones, free trade agreements, etc. — fall under Belt and Road,” Dawn Murphy, an associate professor of national security strategy at the National War College, told Al-Monitor. “Many of the actual activities and foreign policy tools that China includes in Belt and Road actually predate Belt and Road.”

MENA is a keystone of Beijing’s vision for international integration. Its ports and highways link East Asia to Europe and Africa. Roughly 20 million barrels of oil flow through the Strait of Hormuz each day; around 12% of the world’s trade passes through the Suez. The region’s wealthier economies are also valuable wellsprings of investment.

“The Middle East and North Africa are the intersection of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road, and are natural partners for the construction of the Belt and Road,” Xuming Qian, a research fellow at the Shanghai International Studies University, noted.

It is little surprise, then, that Beijing has committed to “coordinating development strategies” and “enhancing cooperation in the fields of infrastructure construction, trade and investment facilitation, nuclear power, space satellite, new energy, agriculture and finance” in the region. The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) policy wonks tiered these areas of interest in a three-step plan dubbed the “1+2+3” strategy — energy cooperation (step 1), enhanced trade and investment (step 2) and collaboration on tech development (step 3).

“China sees this as a way of expanding and solidifying its geopolitical influence and their economic and energy interests in the region,” Dunne remarked.

China’s footprint has only grown more prominent since Xi’s ascendancy. Chinese investors continue to pour cash into the region; the country has been MENA’s leading source of FDI since 2016. Corporate and diplomatic delegations continue to churn out research agreements, construction contracts and investment pacts worth billions. Israel and Jordan are the only two MENA countries that have yet to formally "join" BRI; even so, both are proactively partnering with Chinese firms and fielding Chinese investment. Gradually, some commercial relationships are evolving into strategic ones. Last December, China and Saudi Arabia signed a comprehensive strategic partnership; the Emiratis did the same in 2018. The agreements promised proactive collaboration in tech, energy, finance, and other sectors.

From the perspective of MENA states, the motivations for connecting to China’s network are simple and compelling. According to Gedaliah Afterman, the head of the Asia Policy Institute at the Abba Eban Institute, “there is no other player that can deliver as China is delivering” on trade, investment and infrastructure.

China’s willingness to share its technological expertise befits Gulf regime development plans that hinge on fostering a vibrant tech ecosystem. Wealthier MENA regimes are also eager to send money east. China’s burgeoning refining industry has become a cash cow for Gulf energy firms and deep-pocketed sovereign wealth funds. Two days before Saudi Arabia joined the SCO, Saudi Aramco pledged to invest billions in a Chinese petrochemical firm.

“It’s not just Chinese interests playing out in the Middle East,” Robert Mogielnicki, a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, stressed. “It’s a multidirectional partnership where you’re seeing Middle Eastern interests playing out in China.”

China’s reliance on Gulf energy exports has, in some cases, bred a dependency on Chinese markets. Qatar, for instance, sent 16% of its energy exports to China in 2020; Iran sent close to 20%. For Iran, suffocated by sanctions and isolated from international commercial and financial networks, China is a vital economic lifeline and strategic ally (in 2021, Beijing pledged to dump $400 billion into the country over the next 25 years).

2. Deep Dive: Shifting Priorities

It would be a mistake to assume that China engages all parts of MENA with equal attention and vigor. “There are only a couple of geographic zones within the Middle East that brush up against the main arteries of BRI,” Mogielnicki noted. “The best way to understand Chinese influence in the region is still on the bilateral level.” How does Beijing decide which bilateral partnerships to prioritize? It follows the money. “What are the biggest economies? Where is growth happening? Where is the cash flow? Which countries are generating significant government revenues?”

In recent years, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have emerged as the CCP’s most lucrative partners. The GCC’s flagship members attracted the largest amount of Chinese construction and investment funds in MENA between 2005 and 2022. China sources almost a quarter of its energy imports from Saudi and Emirati oil fields. Last year, China conducted 43% of its MENA trade with the Gulf neighbors. The pair attract a similar percentage of Chinese FDI flows into the region.

“Over the last 10 years, there’s been a shift to more emphasis on the Gulf,” Murphy remarked. “Before 2010, China treated all parts of the region in a similar way.”

The UAE in particular, once a secondary actor, now beckons from center stage. “When China looked around, they saw in the United Arab Emirates a place that was purpose built for connectivity,” Molavi said. In 2014, the Emirates attracted around 14% of Chinese investments in MENA; in seven years, that share more than doubled to 31%.

There are other, more subtle political and economic motivations at play. “In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, China had concerns about the stability of a number of countries,” Murphy said. “China sees the countries in the Gulf as being more stable and larger opportunities from an economic and political standpoint.” Gulf nations are also awash with expendable cash, so Chinese creditors needn’t fret about footing the bill for megaprojects or wading into the toxic politics of debt financing.

Though the UAE and Saudi Arabia attract the bulk of Beijing’s attention, it is keeping other MENA states on its radar. Qatar is an able and eager supplier of LNG and capital. Iraq, another cornerstone of the global energy supply chain, was the top recipient of BRI infrastructure financing in 2021.

Egypt’s command of the Suez and 109 million potential consumers make it fertile ground for Chinese ventures. In 2008, the duo kickstarted the Suez Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone, a sprawling industrial and commercial estate just south of the waterway’s entry to the Red Sea. Investors and businesses have funneled billions into the hub since its conception; just last March, a Chinese piping company agreed to bankroll a $2 billion metal production facility in the zone.

Chinese dignitaries and moneymakers have also flocked to Israel to reap the fruits of its sound regulations, vibrant markets and globetrotting tech sector. Israel attracted 1.66% of Chinese FDI in MENA in 2015; now it claims almost 11%. A $1.7 billion Chinese-operated port opened its docks in the coastal city of Haifa in 2021. Experts suspect negotiations for a Sino-Israeli free trade agreement are in their final stages.

How Beijing pursues economic integration in MENA has also evolved. The "hard" infrastructure projects that once defined BRI’s feverish expansion — roads, ports, etc. — have fallen out of style. Narrower, more technical partnerships are the new vogue.

“There has been a shift to other functional areas, in particular digital cooperation, health and green technologies,” Murphy remarked.

Much of the shift boils down to economics. “There were a lot of willy-nilly deals between 2013 and 2018, where there were infrastructure projects that probably wouldn’t have passed any commercial feasibility test but were financed because you put the BRI label on it,” Molavi noted. “Pre-pandemic, Xi did a health check of Belt and Road projects and saw that there was a lot of quantity but not a lot of quality.”

Doubts about the viability and profitability of these projects festered among the CCP’s highest echelons in the late 2010s. Bleak tales of missed deadlines, crumbling facilities and spiraling debt poured in from across the globe. The financial strains of China’s paralyzing pandemic health measures catalyzed this skepticism.

“It understood that it can’t really carry out the Belt and Road in its initial vision,” Afterman said. “It doesn’t make sense.”

Assessing the progress of Beijing’s early flagship BRI projects in MENA is no easy task. Small whiffs of failure have surfaced. Some construction projects have stalled; others pledges have yet to commence at all. By and large, however, the wealth of China’s most valuable MENA partners has immunized them from the maladies that have afflicted projects elsewhere.

3. The Year Ahead

• Iran is losing its importance in Beijing’s eyes. Investors and businesses are struggling to find opportunities in the Islamic Republic’s weakened economy; domestic instability and inflammatory diplomacy are further dampening its allure. China conducted 15% of its MENA trade with Iran in 2014; that share has since tumbled to 3%. China has also weaned off Iranian fuel. Beijing sourced a mere 0.1% of its energy imports from the country’s sanction-smothered oil fields last year, down from 13.9% in 2002. Beijing won’t write off Tehran completely. The mullahs remain important, loyal (and increasingly pliable) strategic partners. Iran is a large market, and Chinese direct investment remains comparatively high. But Saudi Arabia and the UAE have eclipsed their Gulf rival as China’s primary suitors. “I see China gradually betting on the Sunni countries, on Saudi Arabia and the UAE. That’s a strategic decision,” Afterman remarked. “It doesn’t mean that the Chinese are giving up on Iran, but they see more benefit in investing the same money elsewhere.”

• Whether or not China will leapfrog from its diplomatic escapades with Iran and Saudi Arabia to other regional conflicts is unclear. To some observers, Saudi Arabia and Israel are ripe for normalization; Chinese negotiators could be suitable brokers (and grateful beneficiaries) of this detente. What is more evident, however, is that Beijing will leverage its diplomatic momentum to boost its prominence and profits. “I think you’re going to see a real pickup in the pace of diplomacy undertaken by Beijing, especially in the wake of the Saudi-Iran deal brokered by the People’s Republic of China,” Dunne predicted. “I would also look to see more Chinese diplomatic delegations and business delegations make up for some lost ground [from COVID].”

• The Sino-Gulf partnership will continue to deepen and expand. Both sides are keen on building upon old agreements and spawning new ones. The spring flurry of summits and signings proves as much. “Enthusiasm does vary by country, but in the Gulf in particular, enthusiasm continues to be high,” Murphy remarked.

• Not long ago, the Belt and Road Initiative was geopolitics’ most fashionable catchphrase. Businesses stuffed proposals with the term in hopes of securing loaded contracts. Governments raced to sign on to attract funding and prestige. The project’s failures have since stigmatized the label. Beijing is conscious of its potential toxicity, and it’s launched a rebrand. The CCP piloted the Global Development Initiative and the Global Security Initiative in 2021 and 2022 respectively. The manifestos describing the plans regurgitate many of the BRI’s core principles. “The [BRI] activities may continue, but they may not want to frame it in this way because of the extraordinary levels of criticism they’ve received globally,” Murphy said. Expect a subtle substitution in catchy three-letter acronyms.

4. Case Study: The Digital Silk Road

Beijing unveiled the Digital Silk Road (DSR) in 2015. In the years since its inception, the nebulous program has taken form, supplanting traditional, physical infrastructure projects as the (future) focal point of China-MENA connectivity.

“Cooperation between China and MENA countries in high-tech fields such as 5G, artificial intelligence, big data and cloud computing is developing rapidly and has become a new growth point of the cooperation,” Qian observed.

DSR’s mandate is broad. Its stated purpose is, in large part, to funnel cash into countries striving (and struggling) to develop the industries laid out by Qian. It also bankrolls training centers and exchange programs to transfer Chinese technical expertise to local actors and firms.

For Beijing, DSR presents a fresh avenue toward global economic integration as the BRI’s original routes become cluttered with roadblocks. Erecting a cell tower or sponsoring a data center can purchase the same (if not greater) political and economic clout as a bridge, often with less logistical and financial baggage. “These types of projects are lower risk, and they tend to be more profitable,” Mogielnicki noted. DSR also grants Chinese tech giants the opportunity to box out Western rivals in emerging markets.

Less-developed MENA countries with nascent tech industries and shoddy digital infrastructure have welcomed DSR with open arms. The Gulf’s embrace of Chinese high-tech assistance has been emphatic. “This is a period when [Gulf] countries are coming off of austerity and looking for ways to make government spending more efficient and cut waste,” Mogielnicki added. “The digitization that was going on overlapped quite nicely with that [BRI] shift.”

The Gulf’s eagerness, profligacy and comparative stability have made the region “one of the leading areas of the world where you see the digital silk road becoming a reality,” Afterman said. Saudi Arabia and the UAE both signed agreements with Chinese telecoms behemoth Huawei to develop 5G cellular networks. Chinese firms have also promised to splurge on the Gulf’s glitzy new smart cities. Huawei agreed to construct a 1300 MWh energy storage facility in NEOM, Saudi Arabia’s futuristic city-in-waiting. Alibaba, another Chinese tech multinational, pledged a $600 million investment in a “tech town” in Dubai to house the emirate’s burgeoning tech industry. Space has become a new frontier for cooperation in recent years. Chinese space exploration startup Origin Space announced in mid-March that it planned to open an R&D center in Abu Dhabi. Gulf investors, in turn, have infused Chinese startups and leviathans with generous funding.

DSR has branched into other parts of MENA, too. Israel’s tech sector has received hundreds of millions of dollars of Chinese investment, frightening US policymakers. Turkey and Egypt (in addition to Saudi Arabia and the UAE) have signed DSR-specific MoUs and collaborated with Chinese tech firms.

Renewable energy is another point of convergence in the high-tech space. This month’s Sino-Emirati nuclear power collaboration is but one example. Chinese companies have also invested millions in dozens of solar farm projects across the region in recent years.

5. Key Takeaways

➡ Experts expect China-MENA relations to follow this Gulf-centric, tech-driven path in the years to come. “When China looks 30 years forward, the important players are Saudi Arabia and the UAE, in terms of ability to invest and develop technologically,” Afterman predicted. “They can’t and they won’t focus on these large infrastructure projects as much.” In time, collaborations in health, renewables and the ever-evolving morass of high-tech industries, not just petrochemicals, will glue Asia’s two halves together. Israel, given its technological prowess, may also emerge as a valuable Chinese partner if it can shake the suspicions of its American counterparts.

➡ Israel’s complicated balancing act showcases how geopolitical tensions may derail Sino-MENA integration. “These countries are not into choosing between the United States and China,” Afterman remarked. So far, they haven’t had to commit to one team or the other. But that may change. A full-blown armed conflict between the two superpowers is no longer an aloof, theoretical possibility. “The biggest risk is a broader conflict between the US and China that could really raise the stakes of certain kinds of China-Middle East engagement,” Mogielnicki said. Molavi explained the potential consequences in more dramatic terms: “The current US-China cold war is an irritant for many policymakers in the region, but a real US-China shooting war would be a nightmare.”

➡ Conversely, a convulsion of instability in MENA could scare off Chinese business and investment. “The prospect of instability in the region is something that will really hamper Chinese engagement. The Chinese are very risk averse,” Mogielnicki noted. “They’re not going to rush into conflict zones or even post-conflict zones any time soon, not if there’s money to be made elsewhere.” Progress will only come with peace.

➡ Another complicating factor is China’s uncertain economic trajectory. China’s once awe-inspiring growth is slowing. Its housing boom has cooled, and its workforce population has peaked. Its tech sector — once thought to be on track to match Silicon Valley in size and innovation — is hamstrung by CCP crackdowns on entrepreneurs and stringent regulations on fintech companies. Some China-watchers think the world’s second largest economy has maxed out. A slowdown in productivity and innovation spells worry for the Sino-MENA relationship on multiple fronts. If Beijing finds itself increasingly pressed for cash, it may begin to scale back even its more modest investments and initiatives abroad. If opportunities for investment in China begin to shrivel up, MENA-based funds may begin to write checks elsewhere.

We're glad you're interested in this trend report.

Trend Reports are one of several features available only to PRO Expert members. Become a member to read the full memos and get access to all exclusive PRO content.

Join Al-Monitor PRO Start with a 1-week trial.